Filed under: death metal, Heavy metal, horror literature, Is this where I came from?, sweden | Tags: Clandestine, Entombed, H. P. Lovecraft, Kenny Hakansson, Nicke Andersson, Shadow out of time, Through the collonades, Yngwie Malmsteen

In this 19th instalment of the Is this where I came from series of posts, I present another example of a fantastic death metal song inspired by Lovecraft. These days, every other death metal band has Lovecraftian influences, although it feels more like Lovecraft is used as a promotional vehicle – and a sign of conformity to generic rules – than a genuine source of horror for death metal lyrics. Lovecraftian song titles, album titles, album covers are a trend in contemporary death metal. So, lets go back to a time when masters in their craft, like Keny Hakansson and Nicke Andersson, tapped into Lovecraft’s work to create nightmare sonic landscapes that could send chills down the spine.

H. P. Lovecraft – The shadow out of time

H. P. Lovecraft – The shadow out of time

This is a truly awesome story of alien time-travel, definitely one of my favourite Lovecraft stories, where a human’s body is occupied by the member of an alien Great Race and the human’s mind is displaced into the body of the alien. When the two minds return to their respective bodies the human forgets everything that he experienced whilst occupying the alien’s body for five years, and this period is experienced as amnesia. Eventually, the protagonist of the story starts experiencing dreams of otherwordly vistas in his mind. These dreams end up being memories from when he occupied the alien’s body. The alien realm that the protagonist experienced is described on various instances in the story: “I would seem to be in an enormous vaulted chamber whose lofty stone groinings were well nigh lost in the shadows overhead” (p.478), or, “beyond the colossal stone piers of an enormous town of domes and arches” (p.482). There’s also frequent mentions of the vaults where the histories of stranger worlds and universes – which the Great Race witnessed through the process of mind projection and displacement – are kept archived.

Entombed – Through the collonades

Entombed – Through the collonades

“Through the collonades” was composed by Kenny Hakansson (lyrics) and Nicke Andersson (music) for the album Clandestine (1991). I am pretty sure that Kenny (a “guest” lyricist for the band) drew inspiration from “The shadow out of time” to write this little masterpiece. There is no explicit mention to this story, yet there is ample evidence that supports this hypothesis. The song is about someone who is tormented by otherwordly visions of a terrifying world in their dreams, only to wake up inhabiting this same world. The verse “I close my eyes as if to die, entering again the labyrinths of deep within, beyond where conscious ends”, could be referring to the state of dreaming, leaving consciousness behind and accessing memories of the alien’s realm hidden in the unconscious. The line “the insane watching eye, staring through my bones” could refer to the alien’s projected mind, the alien’s eyes looking through the human’s bodily apparatus. Moreover, the line “shreds the soul out of my skin” could refer to the human body being stripped of the human mind making room for the alien occupation. The song ends with the protagonist waking up finding themselves in the nightmare realm of which they dreamed. Accordingly, near the end of “The shadow out of time”, the protagonist is part of an expedition exploring ancient ruins that resemble the realm of his dreams, and we find the sentences, “My dreams welled up into the waking world”, and “I was awake and dreaming at the same time” (p. 519). It’s such a truly haunting song – especially Andersson’s delivery of the lyrics – that perfectly captures the terror and madness of being confronted with the alien realm.

As a side note, it is also worth pointing out that the word ‘colonnades’ is misspelled on this song. The same misspelling appears on Malmsteen’s song “Judas” from the Eclipse (1990) album. Could be a coincidence, but I think that lots of those early death metal musicians paid attention to what Malmsteen was doing, some of his riffs were massive, and he doesn’t really get much credit for this.

Reference:

Lovecraft, H.P., 2000. Omnibus 3: The haunter of the dark. London: Harper Collins.

Filed under: horror literature, Is this where I came from?, metal, punk | Tags: Anthrax, Blind Guardian, Death alley, Firestarter, Forward to termination, Jack Torrance, Lone justice, Pyrokinesis, Sacrifice, Somewhere far beyond, Spreading the disease, Stephen King, The dark tower, The gunslinger, The shining, zeke

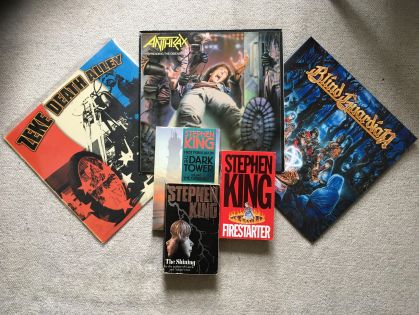

I am currently reading Stephen King‘s book The institute (2019). At the back there’s a biography, where the reader is reminded of King’s influence on wider popular culture, specifically film and TV adaptations of King’s work. What about popular music? In previous posts I have discussed instances of intertextuality between metal music and horror literature, including Clive Barker and Dismember, Dean Koontz and Autopsy, Le Fanu and Mercyful Fate, and the enduring influence of H.P. Lovecraft on death metal. In this new instalment of Is this where I came from? I will talk about Stephen King, one of my favourite horror authors, and his influence on metal culture, specifically on the thematology of metal songs. Many metal bands have been influenced by King’s writings, and here I will present four of my favourite songs by bands like Anthrax, Sacrifice, Blind Guardian and Zeke, that draw on King’s stories.

I am currently reading Stephen King‘s book The institute (2019). At the back there’s a biography, where the reader is reminded of King’s influence on wider popular culture, specifically film and TV adaptations of King’s work. What about popular music? In previous posts I have discussed instances of intertextuality between metal music and horror literature, including Clive Barker and Dismember, Dean Koontz and Autopsy, Le Fanu and Mercyful Fate, and the enduring influence of H.P. Lovecraft on death metal. In this new instalment of Is this where I came from? I will talk about Stephen King, one of my favourite horror authors, and his influence on metal culture, specifically on the thematology of metal songs. Many metal bands have been influenced by King’s writings, and here I will present four of my favourite songs by bands like Anthrax, Sacrifice, Blind Guardian and Zeke, that draw on King’s stories.

1. Anthrax‘s “Lone justice” (1985) – Stephen King‘s The gunslinger (1982)

1. Anthrax‘s “Lone justice” (1985) – Stephen King‘s The gunslinger (1982)

Spreading the disease is by far my favourite Anthrax album. Overall, Anthrax is a band I never particularly liked, but this album was love at first listen. This song specifically is excellent, and undoubtedly my favourite Anthrax song. Awesome opening riff, fantastic verse melody, perfect bridge and one of the most memorable choruses ever. The lyrics tell the story of a solitary man fighting for justice, it could be about anyone, but the mention of “the gunslinger” anchors the song onto the universe of King’s famous sci-fi adventure The gunslinger, the first in the Dark Tower series of books. I have only read the first three books of the series, and I kinda lost interest eventually, but the first two books are great. Anthrax has drawn upon King’s body of work in other instances as well (e.g. “Skeleton in the closet”, “Among the living”), but the result has never been as good as “Lone justice”, in my opinion.

2. Sacrifice‘s “Pyrokinesis” (1987) – Stephen King‘s Firestarter (1980)

2. Sacrifice‘s “Pyrokinesis” (1987) – Stephen King‘s Firestarter (1980)

Sacrifice’s Forward to termination is an amazing thrash album, and the closing track is one of the highlights of the album in my opinion. The lyrics of this song are a direct reference to King’s Firestarter, a story about a little girl who has the power to start fires with her mind. The ability has been passed on to her genetically, as a result of her parents taking part in a series of experiments when they were young. I suppose this album was overshadowed by Slayer’s Reign in blood (1986) and Dark angel’s Darkness descends (1986), two albums that pre-dated it and which clearly left their mark on Sacrifice too, although, to be fair, I wouldn’t be surprised if Sacrifice’s first album influenced Dark Angel to begin with.

3. Blind Guardian‘s “Somewhere far beyond” (1992) – Stephen King‘s The gunslinger (1982)

3. Blind Guardian‘s “Somewhere far beyond” (1992) – Stephen King‘s The gunslinger (1982)

This is another song that is based on King’s The gunslinger. Somewhere far beyond is a monumental masterpiece of an album, not many albums in the history of music are that perfect. The eponymous song is a direct reference to King’s novel, and I can say with conviction that it is a hundred times more legendary than the actual book. It is an absolute roller-coaster of a song, fast, intense, anthemic, displaying different moods. One of my favourite moments on the song is when Roland’s dilemma about whether he should save the boy or go after the man in black is addressed at 3:04 (“…and I don’t care what’s happening to the boy”). The concept of time as it is negotiated in the book, informs another song off this album, namely “Time what is time”, although this clearly also addresses the nature of humanity and the book Do androids dream of electric sheep?.

4. Zeke‘s “Jack Torrance” (2000) – Stephen King‘s The shining (1977)

4. Zeke‘s “Jack Torrance” (2000) – Stephen King‘s The shining (1977)

Although Zeke is primarily a punk band, it is also a heavy rock band, so there you go. I love Zeke, and Death alley (2000) used to be my favourite album by them, until it got dethroned by 2017’s fantastic Hellbender. One of the highlights of this tornado of an album is the song “Jack Torrance”, which gets its name from one of the main characters of King’s The shining. For those who have not read the book, or haven’t seen the film(s), Jack is the caretaker of the Overlook hotel, and he is losing his mind. He is slowly descending into madness, his frail mental health and violent character further taunted by the hotel’s dark forces, and he eventually spins out of control in a frantic murderous rage, resulting in a struggle for survival for his wife and kid. Although this tune represents the madness in Jack’s head sonicaly in a great way, it is also too up-tempo and cheerful to accurately convey the menacing vibe of the book. At the same time it’s a great example of how stories migrate from one form of media to another, and their character changes along this journey.

Filed under: Heavy metal, horror literature, Is this where I came from?, social theory | Tags: Carmilla, In the shadows, Mercyful Fate, Return of the vampire, Sheridan Le Fanu, Vampires

In this, the 15th, instalment of the Is this where I came from? series of posts, I look at one of the very first stories about vampirism in western literature, and one of the very first masterpieces by one of the most important European metal bands of all time. In this instance of intertextuality, I hypothesise that the opening line of Mercyful Fate‘s Return of the vampire has been inspired by Sheridan Le Fanu‘s vampire novella Carmilla.

Sheridan Le Fanu – Carmilla (1872)

Carmilla is a fantastic novella about vampires, written by Sheridan Le Fanu. It constitutes one of the foundational texts that constructed the vampire myth for English readers, alongside Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819) and Stoker’s Dracula (1897). Carmilla has also been transferred to the screen, and its ‘seductive lesbian vampire’ theme underpins various Hammer horror films released in the early 1970s. My favourite of those, and the most loyal adaptation, is The vampire lovers (1970), staring the inimitable Ingrid Pitt. As far as vampire horror goes, this novella has some of the most nightmarish moments I have ever read. The descriptions of Carmilla’s nightly visits to Laura’s bedroom can evoke spine-chilling images. At the end of the story, Le Fanu establishes a direct link between ‘suicide’ and ‘vampires’, which I found very interesting as both things are central signifiers of the goth and emo subcultures. On the last page of the novella, the narrator (i.e. Laura) ponders about, and reveals, the origins of vampires: “How does it begin, and how does it multiply itself? I will tell you. A person, more or less wicked, puts an end to himself (sic). A suicide, under certain circumstances, becomes a vampire“.

Mercyful Fate – Return of the vampire (1981)

“Return of the vampire” is a brilliant song off Mercyful Fate’s third demo. The first time I heard it was not in its original version, but rather the re-imagining of the song on their comeback album In the shadows, from 1993, with Lars Ulrich guesting on drums. The opening words of the song are “A suicide, the birth of a vampire“. This line stuck in my head, yet, it had always been elusive; what does suicide have to do with vampires? It wasn’t until I read Carmilla that I got an answer to this question, as well as a potential intimation of why ‘vampires’ and ‘suicide’ coexist in the goth and emo subcultures. The rest of the song lyrics, albeit full of traditional vampire imagery (i.e. the vampire’s lair, flying in the night, blood-sucking, stake through the heart), do not allude to the Carmilla story.

Filed under: death metal, horror literature, people | Tags: Bone Gnawer, Dave Ingram, Dave Rotten, Echelon, Kam Lee, Putrevore, Revolting, Ribspreader, Rogga Johansson

Fans of underground – and not-so-underground – death metal are familiar with the name Rogga Johansson. He is one of the most prolific death metal musicians in the history of the genre, as he has churned out more than a hundred albums the last 20 or so years. Of course, I don’t mean to suggest that Rogga is solely responsible for the songs on these albums. Each one of them, even albums like the first Bone Gnawer where he wrote all the music, is the result of collaborative effort. By no means I have listened to his entire back catalogue, but I have listened to a good 20-30 albums by bands like Carve, Revolting, Ribspreader, Paganizer, Down Among The Dead Men, The Grotesquery, Echelon, Johansson & Speckmann, Bone Gnawer, Putrevore, and The Skeletal. In many of these bands, he has collaborated with some death metal legends, including Kam Lee (Massacre), Dave Ingram (Benediction), Paul Speckmann (Master) and Dan Swano (Edge of Sanity). In this post I present my five favourite Rogga-related albums. Without further ado, and in order of release:  Ribspreader – Bolted to the cross (2004)

Ribspreader – Bolted to the cross (2004)

Throughout the many years I have been listening to Rogga’s output I have often wondered why have three-four bands that over the years have sounded quite the same, like Ribspreader, Carve, (early) Revolting, and (later) Paganizer. It is not surprising, in my opinion, that the sheer amount of songs in this vein is negatively related to their quality. Nevertheless, the debut album by Ribspreader is an album I really like. Musically, it sounds to me like a mix between early Grave, Edge of Sanity and Death. Dan Swano is part of it, playing drums and guitar. Although overall this is what your average Ribspreader album sounds like, for me it stands out, and I suspect it is because of Swano. The latter has been one of my favourite musicians of all time, and there is no doubt that he has contributed some classic EOS-sounding riffs and melodies in this little monster (for example, the first riff off “Beneath the cenotaph” or the harmony before the fast part in “Heavenless” could have easily been on the first two EOS albums). Lyrically, the album is about death, the afterlife, and religion. It is no secret that Rogga tends to be repetitive, and songs like “Dead forever” and “Morbidity awoken” are a case in point, where the same lyrics are featured in the choruses of both songs, on the same album. I love the nightmarish cover. All songs are awesome, but right now my favourite tracks would be “Dead forever”, “Morbidity awoken”, “Hollow beliefs”, “Sole sufferer”.

Bone Gnawer – Feast of flesh (2009)

Bone Gnawer – Feast of flesh (2009)

With Bone Gnawer, Rogga continues the trend of collaborating with death metal legends. Their debut is a meat-and-potatoes death metal album, super catchy, and its highlight is without a doubt Kam Lee’s excellent performance. The songs are generally mid-paced, with skunk-beat and rare blast-beat explosions. At times it is reminiscent of old Six Feet Under, especially in the repetitive and minimalist chorus of songs like “Hammer to the skull”. At other times it even reminded me of Cannibal Corpse, or Massacre (for example on the fast bits of “Cannibal cook-out”). Lyrically, Lee draws on horror cinema thematology, and cult movies of the genre like The Texas chainsaw massacre 2, Anthropophagus, The hills have eyes, and Cannibal Holocaust. Favourite tracks include “Sliced and diced”, “Cannibal cook-out”, “Lucky ones die first” and “The saw is family”.

Putrevore – Tentacles of horror (2015)

Putrevore – Tentacles of horror (2015)

Putrevore is one of the most brutal of Rogga’s bands, if not the most brutal. The band’s sound hints to US bands like Incantation and Rottrevore (duh!). In this band Rogga collaborates with another central figure of brutal death metal, namely Dave Rotten, owner of Repulse records and Xtreem music, and frontman of Avulsed, among other bands. Rotten has done some pretty unorthodox things vocally, even by death metal standards (I still piss myself laughing whenever I hear the opening track of Christ Denied‘s Cancer eradication album). Here, his filthy growls perfectly complement the swampy and majestic compositions. This album is the most clean sounding in this band’s discography. Here the lyrics deal with horrors found in Lovecraftian mythology. Preoccupation with this mythology also happens in other of Rogga’s bands, including Revolting, and, in a more subtle way, The Grotesquery, another band in which he collaborates with Kam Lee (and whose first album is another very good one!). It’s hard to say which my favourite songs are, as all of them are awesome, and each one feels like part of a greater whole, but I’d say “The rotten crawls on” is memorably awesome.

Echelon – The brimstone aggrandizement (2016)

Echelon – The brimstone aggrandizement (2016)

This is one of the several among Rogga’s bands that the inimitable Dave Ingram handles the lead vocals. Ingram and Johansson have collaborated in other bands as well, and another album I like is the second by Down Among the Dead Men. Lyrically, Ingram engages with satanic texts as well as the Dr Who universe (Whoniverse?) I think, neither of which interest me. But, his delivery, his vocal patterns, and his ad libs are phenomenal. The song-writing is relatively diverse; there are fast and slow songs, lots of d-beat, some blast-beats lots of fast tremolo picking, and some melodies that would not be out of place in Gothenburg death metal. Songs that I think stand out include the strange and brilliant metalised punk number “Monsters in the gene pool/Sonic vortex” (it could have been written by The Plasmatics), “Vital existence”, as well as the absolutely devastating “The brimstone aggrandizement”. This is an awesome album, but I still think that the best post-Benediction album that Ingram did is Downlord‘s Random dictionary of the damned, a true masterpiece, and one of the most under-appreciated death metal albums of all time.

Revolting – Monolith of madness (2018)

Revolting – Monolith of madness (2018)

Revolting’s most recent album is an easy choice. The band has had a steady line-up throughout the years, and Rogga, like in many of his bands, handles the lead vocals and guitar. It is one of his most catchy albums, with awesome melodies and hooks and I love it. This is the only one in the list that doesn’t feature a death metal “superstar”. Lyrically, once again you have the Lovecraftian references (to be honest, these days I’m getting sick of them – every other death band has some meaningless tentacle reference) and gory horror references. Definitely the most easy-listening album on this list, and my favourite among all the Revolting albums I have listened to. You can read a more detailed review of it at the end of the post about my favourite albums from 2018.

Rogga Playlist

Filed under: death metal, horror literature, internet and music, popular music, sweden | Tags: Alex Hellid, August Derleth, Clandestine, E. A. Poe, Entombed, H. P. Lovecraft, Kenny Hakansson, Lars Rosenberg, Nicke Andersson, The masque of the red death, The mummy, Tomas Skogsberg, Uffe Cederlund

Recently a colleague started an Album Club, inviting people to suggest one album that they would like to get together to listen to and talk about. Nobody from work listens to – or at least is a committed fan of – metal so I thought I should introduce them to some excellent masterpiece from my favourite genre. I considered several albums that are sublime and which I think everyone should hear, such as Death‘s Symbolic (1995), Dismember‘s Massive killing capacity (1995), At The Gates‘s second (1993) or fourth album (1995), Blind Guardian‘s Imaginations from the other side (1995), Iron Maiden‘s Somewhere in time (1986), Paradise Lost‘s Draconian times (1995), Napalm Death‘s Enemy of the music business (2001), Carcass‘s Heartwork (1993), Sinister‘s Diabolical summoning (1993) and Slayer‘s Seasons in the abyss (1990). In the end, I decided to go with Entombed‘s Clandestine (1991), an album I love as much as all the previously mentioned, and maybe a bit more. This is a post about the rich culture of Clandestine, which I also aim to share with my colleagues in the context of this Album Club.

As with many death metal albums, Clandestine is an artifact situated at the intersection of horror literature, horror cinema and death metal music. Influences from at least those three fields have been drawn to create what Clandestine is. As such, maximising the pleasure derived from Clandestine requires, first of all, attunement to the compositional conventions of the death metal genre. I consider the latter necessary for navigating the soundscapes created by fast tempos, absence of traditional popular music compositional templates, fast tremolo picking, growled vocals, heavily distorted guitar sound, and so forth. Albums that I consider important stations towards Clandestine include Black Sabbath‘s Master of reality (1971, “Evilyn” – especially the last verse – bears the mark of the riff and groove of “Children of the grave“), Slayer‘s Reign in blood (1986, from which “Chaos breed” borrows the evil melodies and backwards gallop of “Raining blood“), Death‘s Scream bloody gore (1987, from which Clandestine took… well, death metal) and Leprosy (1988, from which Clandestine borrowed fast tremolo-picked riffs like the main one of “Born dead“), Carcass‘s Symphonies of sickness (1989), Autopsy‘s Severed survival (1989, for the fast tremolo-picked riffs on songs like “Disembowel“), Atheist‘s Piece of time (1989) and Atrocity‘s Hallucinations (1990, from which Clandestine borrows the compositional complexity, and in the case of Atrocity the beginning of “Defeated intellect“, and the disturbing melody at the beginning of “Hallucinations“), as well as more generally bands like Discharge and GBH (from which Clandestine borrows the D-beat heard on “Sinners bleed and “Blessed be“). Experience with the aforementioned albums/bands would build a degree of familiarity with the style which would then render Clandestine more decipherable, both in terms of musicality but also in terms of how an album like this came about.

Horror movie samples are integral to the album’s soundscape. The awesome quotes from The masque of the red death (1964) (i.e. “There is no other god! Satan killed him”, “Each man creates his own heaven, his own hell”, “Death has no master”), itself a film based on E. A. Poe‘s story of the same name, are recruited in the opening song “Living dead” to complement Alex Hellid’s anti-christian discourse. As a horror movie fan I discovered some of those references accidentally over the years. The insane laugh in “Sinners bleed“, arguably one of the most haunting moments of the album, comes from the classic horror movie The Mummy (1932), as well as the sampled words “death…eternal punishment”, which precede the aforementioned laugh (at 3:05). In these occasions, the band takes texts found in films, edits, remixes and adds them to their compositions to animate horrifying sensations.

“Death… eternal punishment… for anyone who opens this casket. In the name of Amon-Ra… the king of the Gods”

Lovecraftian terror underpins some of the album’s lyrical thematology and visuality. “Stranger aeons” deserves special mention in this context. It is a song which for many years I did not consider on par with the rest of the songs on this album; it is slow, not as complex as the other songs, and it had that riff that whenever I would hear it I would think of “Ruptured in purulence” by Carcass. Over the years, and by building cultural competences in the field of horror literature, I learned how to love it. The intentional Lovecraftian references include the title, as well as the lyric “lurking at the threshold, you’re lost between the gates”. The latter refers to the book The lurker at the threshold written by August Derleth, based on H. P. Lovecraft‘s universe and some of his unfinished work. Interestingly, and this is where a person’s idiosyncrasy kicks in to continue the cultural production, much of the imagery that’s invoked while listening to this song was not intentionally encoded in the lyrics but inadvertently found its way in. For example, discursive fragments by stories like ‘The thing on the doorstep’ or ‘The lurking fear’ also come to mind when I listen to this song. I literally think of Edward’s liquefied body at the threshold of the house as described in the former, an image that produces a horrifying sentiment, which I don’t think was the intention of Kenny Hakansson when he wrote the lyrics. In such occasions I become a cultural poacher, combining disparate texts in unintended ways to experience unique pleasures.

“Through the collonades” (a misspell of the word colonnades) is the closing song of this extremely thickly textured and complex album, a breathtaking song that has been transformed for me over the years. Although musically it always fascinated me, the cultural input that encouraged me to engage with the lyrics was Lovecraft. When I first listened to Clandestine in the mid-1990s I had not read Lovecraft yet. Only ex-post I can tell that reading those lyrics back in the day did not invoke a visual narrative in my mind, besides the image of walking down a dark path flanked by tall colonnades. It was reading Lovecraft, and especially tales like “The crawling chaos” (co-written by Winifred V. Jackson), that eventually allowed me to produce a coherent tale and a visual landscape in my mind. I love how the mood shifts from sombre to urgent and panicky as the narrator begins to describe the horrors s/he encountered (at 3:08 – “hellish terror risen in the mountains of unknown”). Finally, the horror of waking up from a nightmare only to discover you live in another one is a very Lovecraftian one, and the lyric line “although my dreams have ended, as I wished in weakened thought, beyond the night is total and through the collonades I walk” sends chills down my spine. It also brings into mind the Lovecraftian John Carpenter film In the mouth of madness (1994), where the boundaries between nightmare and reality blur, and the terror of waking up to a nightmarish reality is ever-present.

The above are merely a few of the things that explain my fascination with this album. What this account does not include is the memories from countless hours of listening to it, alone and with friends, for the past 24 years, and of course the pleasure of engaging with this album, both in terms of seeking to learn new things about it, and in terms of surrendering to its magic and allowing it to carry me away into its strange universe.

The entire Clandestine live in 2016

Some of the scholarly ideas that underpin the above narrative can be found in the following:

Bourdieu, P. (1984), Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. London: Routledge.

Jenkins, H. (1992), Textual poachers: Television fans and participatory culture. London: Routledge.

Filed under: death metal, horror literature, Is this where I came from? | Tags: album covers, Cancer, death breath, Deceased, Dreadful pleasures, Haunted, horror cinema, Humanoids from the deep, Luck of the corpse, Revolting, six feet under, Stinking up the night, The haunting of Morella, The plague of the zombies, To the gory end

The relationship between horror cinema and death metal is a complicated one.The orthodox and not particularly critical way to approach this relationship is to resort to the so-called birth of heavy metal in the late 1960s. If Black Sabbath is the band that captured the imaginations of musicians, music journalists, and fans who co-created the genre we know as heavy metal, then it makes sense to argue that horror cinema is a cornerstone of the genre. Black Sabbath got its name from the Mario Bava classic horror anthology from 1963. Moreover, the band supposedly made the conscious decision to write songs that would constitute the equivalent of horror cinema in the music industry.

The relationship between horror cinema and death metal is a complicated one.The orthodox and not particularly critical way to approach this relationship is to resort to the so-called birth of heavy metal in the late 1960s. If Black Sabbath is the band that captured the imaginations of musicians, music journalists, and fans who co-created the genre we know as heavy metal, then it makes sense to argue that horror cinema is a cornerstone of the genre. Black Sabbath got its name from the Mario Bava classic horror anthology from 1963. Moreover, the band supposedly made the conscious decision to write songs that would constitute the equivalent of horror cinema in the music industry.

In line with this tradition, horror cinema has been an integral part of death metal lyrically, visually, and musically. Some of the seminal musical and lyrical death metal texts reference horror cinema directly. Possessed‘s influential debut Seven churches from 1985 kicks off with the song “The Exorcist“, incorporating both the title and theme tune of the groundbreaking horror film from 1973, albeit slightly altered presumably to avoid copyright issues. Another foundational death metal album, Death‘s debut Scream bloody gore (1987) includes the song “Evil dead“, whose title refers to the cult horror by Sam Raimi, and the intro melody is a cover of the theme tune of Zombi, the cult zombie-gory-horror film by Lucio Fulci. Deicide‘s debut (1990) also references Evil Dead in the song “Dead by dawn“. The homonymous song off Entombed‘s debut, Left hand path (1990), concludes with a version of the theme tune from Phantasm (Entombed has used dialogue samples from horror cinema in many other albums, including on Clandestine (1991), Wolverine blues (1993) and Morning star (2001)). It could be argued that horror cinema references were early on established as canonical for new occupants/creators of the death metal genre.

Many death metal bands have used the imagery of horror films in their album artworks. Cancer‘s awesome debut, To the gory end (1990), a cornerstone of British death metal, references the gory and influential sequel to Night of the living dead (1968), Dawn of the dead (1978), with its cover artwork which depicts the famous zombie with a machete slicing its head, making it one of the most identifiable death metal covers of all time.

Deceased‘s supercharged debut album, Luck of the corpse (1991), portrays on its cover the corpse of the medium from “The drop of water”, one of the tales from Mario Bava’s Black Sabbath (1963). The terrifying dead medium is one of the most nightmarish characters in the history of horror films, and in my opinion does not fit the intense death-thrash of the album. I would expect something much darker and claustrophobic from an album with this cover, something more akin to early Asphyx or early Benediction.

Six Feet Under‘s classic now debut from 1995 is full of references to murder and classic horror themes, such as zombies (“Torn to the bone”, “Still alive”) and werewolves (“Lycanthropy”). The cover of the album has been taken from the poster of the 1990 Gothic horror The haunting of Morella, a film loosely based on a story by Edgar Alan Poe. In spite of what I thought were silly performances, awkward sound and editing, and messy direction it is a wildly entertaining movie. The cover is a brilliant painting that fits the style of the album well; I truly feel haunted when I’m listening to it. Obviously, the title of the album, Haunted, also alludes to the film.

Death Breath was a breath of fresh stinking air in the early days of the somewhat mediocre resurgence of old-school Swedish death metal. What better way to celebrate Nicke Andersson’s return to death metal than to reference some old-school horror cinema! Death Breath’s self-titled EP and debut album from 2006 reference the classic Hammer horror The plague of the zombies (1966). The iconic zombie with the empty eyes and the grotesque snarl is to this day one of the most terrifying monsters in film, and stands in sharp contrast to the rest of the film, which is not particularly frightening in my opinion. By the way, if you haven’t seen the video that the band made for the homonymous song do yourselves a favour and watch it; pure Night of the living dead worship!

Revolting is another new “old school death metal” band par excellence. Accordingly in its debut titled Dreadful pleasures (2009) it references an old school horror film titled Monster, also known as Humanoids from the deep (1980). Revolting might not be of the order of old school death metal bands like Death, Deicide, Cancer, and Entombed, but Humanoids from the deep is a great movie that truly stands out. Alongside the usual horror tropes (stalking, people murdered one after the other, gore, nudity) this movie has great cinematography and an interesting plot. The artwork is pretty cool too.

Filed under: death metal, horror literature, Is this where I came from? | Tags: Clive Barker, Dismember, Hallucigenia, massive killing capacity, Richard Cabeza, The great and secret show

The newest installment in this series of posts is about a band and an author I admire a lot. I have loved Dismember since my early teenage years in the mid 1990s, and Clive Barker is an author who I admired first as the writer/director of the first Hellraiser film, one of the absolute masterpieces of horror cinema, and then as a unique horror writer. The song “Hallucigenia” by Dismember was probably influenced by Barker’s book The great and secret show.

Clive Barker – The great and secret show (1989)

Clive Barker – The great and secret show (1989)

The great and secret show is the first part of an unfinished trilogy known as “the art”. In this fantasy/horror Barker weaves a complex story about the battle between two evolved beings (that once were human) over the space (i.e. Quiddity) between our world (i.e. Cosm) and the afterlife (i.e. Metacosm). One of the two beings is the Jaff (or, his human name, Jaffe), who is drunk with power and has evil intent, and the other one is Fletcher, who wants to protect Quiddity from the Jaff. The Jaff has the ability to extract from people their primal fears, materialised as monsters that he calls terata (the Greek word for monsters), and Fletcher has the ability to bring into existence people’s fantasies, what he calls hallucigenia. By raising Hallucigenia he forms his “army from the fantasy lives of the ordinary men and women he met as he pursued Jaffe across the country” (p.64). At some point in the story (after page 367) the fantasies of many of the residents of Palomo Grove, touched by Fletcher’s power, come into existence. Many of those fantasies are of sexual nature, leading many of the people isolating themselves in their homes reveling in sexual debauchery with their hallucigenia.

Dismember – Hallucigenia (1995)

Dismember – Hallucigenia (1995)

Dismember’s “Hallucigenia” is a song composed by Richard Cabeza, and it is one of the most fantastic songs off Massive killing capacity, and a cornucopia of references. It kicks off with a brilliant, creepy Autopsy-like melody, leading to an up-beat Venom-sounding chord progression (I’m thinking “Countess Bathory”) that is repeated during the chorus, ending in a similar way to Kiss‘s “Black Diamond”. The song title and lyrical content refer back to Clive Barker‘s The great and secret show. After reading Barker’s book and realising the connection, and after listening to this album for 23 years, the lyrics suddenly made sense! The protagonist of the song is someone who apparently fantasised about sexual debaucheries with demons. Hallucigenia refers to these fantasies coming to life.

Lyrics: “On my throne of sin, I watch the demons feed, nails cut deep into my flesh, and release my pulsing blood. Serpents dance before my eyes, and tempt the lust inside, let me taste the pain, devour me, my wicked queen! Whip me with chains of sin, let your jaws open my skin, lips and tongues licking the wounds, in ecstasy I’ll rise. Whores of hell, demons appear to feast on my flesh, bleed with me, souls forever free. Taste the pain and the desire, like a drug it’s my need, bleeding bodies, endless orgies, in carnal blasphemy.”

Filed under: death metal, horror literature, Is this where I came from? | Tags: autopsy, Dead, Dean Koontz, Mental funeral, The eyes of darkness

This series of posts has traditionally been about obscure examples of musical intertextuality across genres. I have so far discussed several examples of riffs, melodies and song structures traveling through time and space; from 1970s English Hard rock to 1990s Swedish Death metal (#5), from 1980s Irish Shoegaze to 1990s US Progressive metal (#3), from 1990s Welsh Alternative rock to 2000s German punk (#8), and others. In this, the 10th installment, I will do something slightly different. I will focus on song lyrics (as I have done in the past in a post on H.P. Lovecraft) and I will hypothesise that Autopsy got the idea for the song “Dead” from a section of Dean Koontz’s book The eyes of darkness.

Dean Koontz – The eyes of darkness (1981)

Dean Koontz – The eyes of darkness (1981)

For a long time I considered Koontz a horror/mystery writer who was good, but by no means of the order of Clive Barker or even Stephen King. That opinion changed when I read the absolutely fascinating Phantoms (1983), a book whose plot is amazing, the different avenues that the plot follows and the crossroads on which these avenues meet is mind-blowing, and it is quite gruesome as well. The eyes of darkness is a book that was definitely enjoyable, but nowhere near as good as Phantoms. It is about a mother who tries to solve the mystery around her son’s death. I will not go into more detail because the plot is irrelevant to the aim of this post. What is relevant to this post is a description of the protagonist’s dead son on page 6:

“Torn and crushed in a bus accident with fourteen other little boys, just one victim of a larger tragedy. Battered beyond recognition. Dead.

Cold.

Decaying.

In a coffin.

Under the ground.

Forever.”

Mental funeral is an unprecedented masterpiece, and my all-time favourite Autopsy album. The song Dead is a strange song, in that its lyrics are just 10 words, morbidly narrated (and written) by Chris Reifert, on top of a gruesome riff. The melody preceding and then following the narration proved to be an extremely influential one in the death metal genre, with countless bands imitating it (you can hear the similarity on Entombed‘s “Somewhat peculiar“). The muddy composition, the singing style and the lyrics make it one of the most memorable and creepy songs in one of the most memorable and creepy albums of all time. The lyrics/theme are almost identical to the short text by Dean Koontz:

“Dead.

Stiff and cold.

In your box.

To decay.

Dead.”

Filed under: death metal, horror literature, people | Tags: Dan Seagrave, death breath, death metal, Entombed, H.P.Lovecraft, Iron Maiden, Massacre, Metallica, Morbid Angel, Morbus Chron, Morgoth, Nile, Septic Flesh, Sinister, therion, Tiamat

After a long time I decided to revise this post about the influence of H.P. Lovecraft’s body of works on the Death Metal genre. When I first wrote it back in 2009 I had just started delving into the wonders of Horror literature. I rediscovered Stephen King, some of whose works I read back in the 1990s, and I quickly found books by Clive Barker and H.P.Lovecraft, two other great figures of Horror literature. My interest in the horror genre was not accidental. Having grown up listening to Heavy metal, I was inadvertently exposed to horror literature references. My first Heavy metal CD ever was Iron Maiden‘s Live after death. The thing that first mesmerised me before even listening to the music, was the amazing cover. On the tombstone, a quote from Lovecraft’s Call of Cthulhu is inscribed: “That is not dead which can eternal lie, yet with strange aeons even death may die”. Part of my interest in exploring those references in more detail stemmed from my desire to understand my favourite musicians a bit better, and connect with them on an abstract cultural plane. Another factor that enabled this obsession with horror literature is the availability of extremely cheap books in England. I have bought almost all my books from local charity shops, and each book has cost me between 50p and £2. Finally, my interest in horror literature can also be linked to my fascination with horror movies, which goes back to my early childhood. I remember being in the early grades of primary school and watching The Hand (1981), together with my mom, or The Blob (1986) without my parents knowing, or Poltergeist III (1989) and not being able to sleep, or being 9-10 years old and looking forward to Friday night to watch the new episode of Friday the 13th the TV series (and talk about it with my cousin George next time we’d meet).

As Roland Barthes has pointed out, all texts refer only to other texts. This post is about Lovecraft’s influence on various texts (i.e. lyrics and images) associated with the Death metal genre.

Nile‘s first full length, Amongst the Catacombs of Nephren-Ka (1998), is my personal favourite Nile album and a true gem of mid- to late 1990s American brutal death metal. Both the words “Nile” and the title of the album can be found in the same sentence at the end of the haunting short story by Lovecraft, “The Outsider”. The catacombs are the home of the deformed creature which has dwelled there mummified for centuries, before it ventured to visit the outside world. The catacombs are the place where the creature returns after realising its abominable existence. Another noteworthy example, as pointed out by one of the readers of the blog, of Lovecraft’s influence on Nile’s music is the monumental “4th Arra of Dagon” off Those whom the gods detest (2009).

Nile‘s first full length, Amongst the Catacombs of Nephren-Ka (1998), is my personal favourite Nile album and a true gem of mid- to late 1990s American brutal death metal. Both the words “Nile” and the title of the album can be found in the same sentence at the end of the haunting short story by Lovecraft, “The Outsider”. The catacombs are the home of the deformed creature which has dwelled there mummified for centuries, before it ventured to visit the outside world. The catacombs are the place where the creature returns after realising its abominable existence. Another noteworthy example, as pointed out by one of the readers of the blog, of Lovecraft’s influence on Nile’s music is the monumental “4th Arra of Dagon” off Those whom the gods detest (2009).

Morbid Angel, the cornerstone of American brutal death metal, is clearly guided by Lovecraft. References to the Ancient Ones and Yog-Sothoth, characters built around the Cthulhu mythos, are ubiquitous in all Morbid Angel discography, especially in albums Blessed are the sick (1991) and Formulas fatal to the flesh (1998). Morbid Angel not only write lyrics inspired by Lovecraft, but also their philosophical explorations draw on the mystical cosmos created by Lovecraft; what constitutes reality; which part of reality the human mind can perceive and what its limitations are; how the human mind is bound by social and cultural norms prohibiting us from accessing other realities, and so forth.

Morbid Angel, the cornerstone of American brutal death metal, is clearly guided by Lovecraft. References to the Ancient Ones and Yog-Sothoth, characters built around the Cthulhu mythos, are ubiquitous in all Morbid Angel discography, especially in albums Blessed are the sick (1991) and Formulas fatal to the flesh (1998). Morbid Angel not only write lyrics inspired by Lovecraft, but also their philosophical explorations draw on the mystical cosmos created by Lovecraft; what constitutes reality; which part of reality the human mind can perceive and what its limitations are; how the human mind is bound by social and cultural norms prohibiting us from accessing other realities, and so forth.

Entombed‘s masterpiece Clandestine (1991) contains the song “stranger aeons“. The lyrics are written by Kenny Hakansson. Phrases like “stranger aeons” and “Stranger things that eternal lie” point towards the Cthulhu mythos once again. Other phrases like “lurking at the threshold” also point to other Lovecraft tales like the Thing at the Doorstep, or The Lurker at the Threshold (mainly written by August Derleth). The painting by Nicke Andersson at the back cover of the album, depicts a head with frightening hollow eyes and tentacles, reminiscent of Lovecraft’s ancient God Cthulhu.

Entombed‘s masterpiece Clandestine (1991) contains the song “stranger aeons“. The lyrics are written by Kenny Hakansson. Phrases like “stranger aeons” and “Stranger things that eternal lie” point towards the Cthulhu mythos once again. Other phrases like “lurking at the threshold” also point to other Lovecraft tales like the Thing at the Doorstep, or The Lurker at the Threshold (mainly written by August Derleth). The painting by Nicke Andersson at the back cover of the album, depicts a head with frightening hollow eyes and tentacles, reminiscent of Lovecraft’s ancient God Cthulhu.

In 2006 Death Breath from Sweden released the excellent album Stinking up the night. The album closes with a haunting instrumental titled “Cthulhu Fthagn”. The song is apparently a tribute both to Lovecraft and Metallica, who had recorded the instrumental “The call of Ktulu” in their Ride the lightning (1984) album. These words (cthulu fthagn) are what Wilcox the sculptor heard, during his horrifying dreams of the city where Cthulhu slept. In the same album, the song “A morbid mind” also refers to the Lovecraftian mythology, and ”Flabby Little things from Beyond” refers to the short story From Beyond where a scientist creates a device that allows people to perceive hidden dimensions. Massacre‘s first album From Beyond (1991), one of the ultimate Death Metal albums, is dedicated to this story as well. What I have identified as Lovecraftian references in Tiamat‘s work, are a bit more obscure. The title “In the shrines of the kingly dead”, off Tiamat’s debut album, alludes to the terrifying story The hound, where the phrase “the narcotic incense of imagined Eastern shrines of the kingly dead” can be found. The story Celephais includes the recurring phrase “where the sea meets the sky”, and a similar phrase is also found in Tiamat’s “A caress of stars” off Clouds (1992).

Other references to Lovecraft come from bands like Therion, and their song “Cthulu“, off their fantastic second album, Gutted‘s “Nailed to the cross”, a strange blend of Lovecraft and anti-christian lyrics off their debut album Bleed for us to live (1994), and Sinister‘s “Awaiting the Absu”, from their masterpiece Hate (1995). In the eponymous track of Septic Flesh‘s first album (i.e. Mystic places of dawn (1994), one of the superior albums in death metal history, or even music history overall), there is the lyric “… Sarnath the doomed, and names that echo in the labyrinths and the cavernous depths of chaos”. This is a reference to the short story “The doom that came to Sarnath”, which talks about an imaginary city that prospered after ravaging an ancient alien race, which eventually returned to take revenge. The song “Lovecraft’s death” off Communion (2008) is full of references to stories such as The rats in the walls, The whisperer in darkness, and The music of Erich Zann, among others.

Other references to Lovecraft come from bands like Therion, and their song “Cthulu“, off their fantastic second album, Gutted‘s “Nailed to the cross”, a strange blend of Lovecraft and anti-christian lyrics off their debut album Bleed for us to live (1994), and Sinister‘s “Awaiting the Absu”, from their masterpiece Hate (1995). In the eponymous track of Septic Flesh‘s first album (i.e. Mystic places of dawn (1994), one of the superior albums in death metal history, or even music history overall), there is the lyric “… Sarnath the doomed, and names that echo in the labyrinths and the cavernous depths of chaos”. This is a reference to the short story “The doom that came to Sarnath”, which talks about an imaginary city that prospered after ravaging an ancient alien race, which eventually returned to take revenge. The song “Lovecraft’s death” off Communion (2008) is full of references to stories such as The rats in the walls, The whisperer in darkness, and The music of Erich Zann, among others.

Another amazing song coming from recent years, is Morgoth‘s “Nemesis” off their awesome comeback album Ungod (2015). The lyrics of “Nemesis” come from Lovecraft’s homonymous poem, and I cannot imagine a better soundscape for it. Another relatively recent example of Lovecraftian death metal comes from Morbus Chron. Their first album includes the brilliant song “Red Hook horror“, which references The horror at Red Hook, one of the most talked-about Lovecraft stories. It is one of the stories that have been identified as an example of Lovecraft’s xenophobic and far right beliefs, as it is laden with derogatory epithets and imagery about US immigrants and the economically deprived. Morbus Chron have borrowed minor elements of the story and created their own vague, gruesome narrative.

The art of Dan Seagrave, one of the most important painters-cover artists of the death metal genre, clearly draws on Lovecraft’s imagination. Much of his more recent work, finds the artist obsessed with bizarre architecture (i.e. “non Euclidian geometry”), of the kind mentioned in the dreams of Lovecraft’s characters of the city R’lyeh. Looking at covers like Morbid Angel‘s Gateways to Annihilation (2000) or Suffocation‘s Souls to Deny (2004), can only bring into mind descriptions from the Call of Cthulhu like, “…great Cyclopean cities of Titan blocks and sky-flung monoliths…”.

Some of the readers of this blog have made some contributions in the comment section, so please read on for more Lovecraft influences! To be continued…